This article is about the construction of Mormon temples, of which The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints operates more than 140 across the globe. Temples are not the same as Mormon chapels, where Latter-day Saints go for weekly worship services each Sunday. Temples are closed on Sundays, and only Mormons living the highest standards of the faith can enter a temple after its dedication.

In Australia, there are five Mormon temples, one in each of the mainland state capitals. The first temple was constructed in Sydney in the early 1980s. The other temples were constructed since the year 2000. Before the Sydney temple was built, Australian members had to travel to the New Zealand temple in Hamilton to participate in the highest ceremonies of the Mormon faith. These include marriages for eternity (as distinct from marriages 'till death us do part') and other ceremonies which ensure that families will be united both in this life and the hereafter.

After 25 years on the job, steelworker Lec Holmes is an expert in his field. But as he helps construct The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ second temple in Provo, Utah, he admits it’s “not like a typical [construction] job.” Not typical because of its steep pitched roofs (he’s used to square buildings with flat roofs). Not typical because of the unity among the various parties involved in construction (he says “everybody gets along”). Not typical because Mormon temples are built to the highest standards (he notes that workers at the Provo site are “more conscious on the quality of work that's done here”).

Indeed, for those who live near them, the Church’s completed temples are “beautiful” structures, meant to last hundreds of years thanks to their high-quality materials and rigorous building standards.

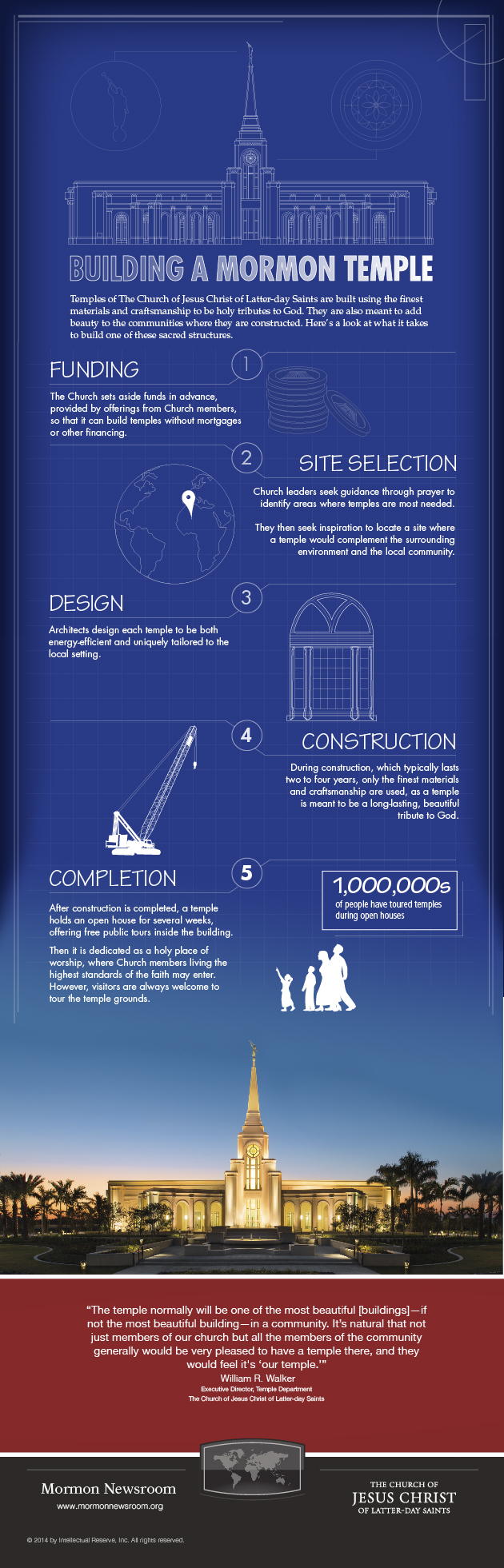

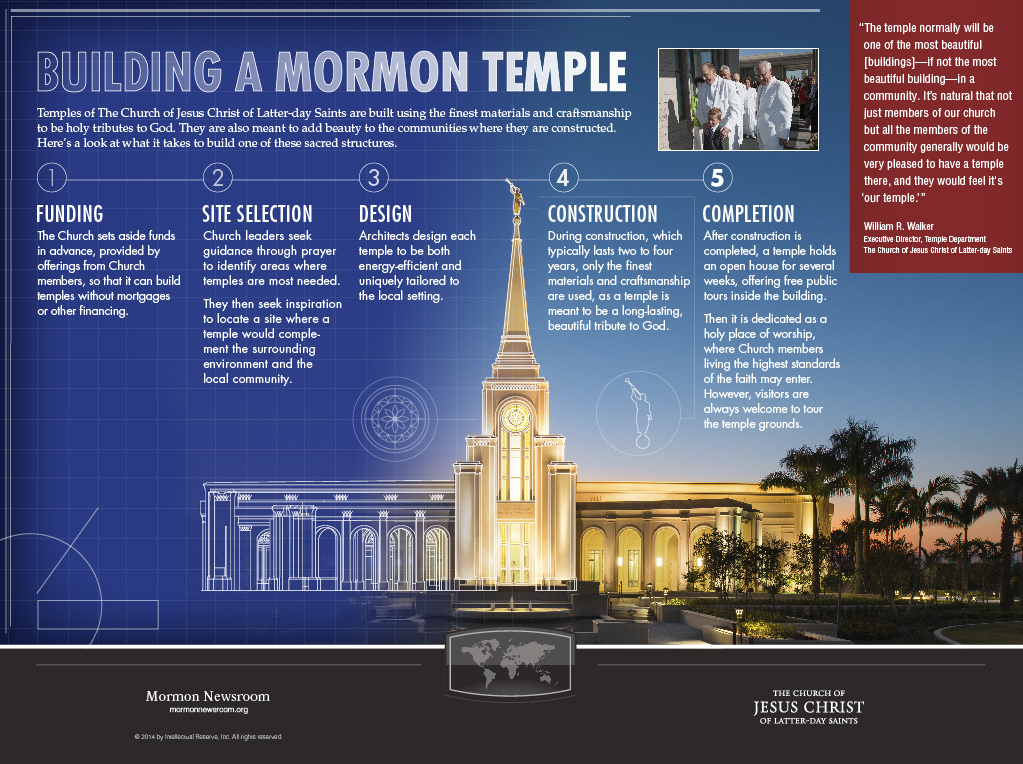

This document explains the process of building a Mormon temple from start to finish. It shows that the creation of these sacred structures is much like the construction of any other building (leaders identify a need and select a site, and architects design and contractors build), but it is also unique in many ways because of the significant role temples play in Latter-day Saint theology.

Funding, Identifying a Need and Selecting a Site

First, it’s important to note that Mormon temples are built using Church funds set aside for that purpose and that the Church pays for the costs without a mortgage or other financing. “We’ve had a long-standing practice in the Church for well over 100 years that we don’t take loans or put mortgages on properties to build temples,” says Elder William R. Walker, executive director of the Church’s Temple Department. “So we would not build a temple unless we could pay for the temple as the temple was built.”

The Church seeks to provide opportunities for Mormons across the globe to access its temples. Eighty-five percent of members live within 200 miles (320 km) of a temple, and temple sites are generally located in areas with enough members (there’s no required number) to warrant construction, or where great distances exist between temples. Public announcements for new temples are usually made by the president of the Church at a general conference.

- kansas-city-temple-gold-leaf

- Provo-CC-Temple3

- brigham-city-temple-construction

- brigham-city-temple-chandelier-2

- brigham-city-temple-chandelier

- cebu-temple-construction

- Gilbert-temple-construction-blue-sky

- Oquirrh-Mountain-temple-construction

- Rome-Mayor-tour-Temple1

- provo-city-center-temple-construction

- provo-city-center-temple-construction-baptistry-plan

- provo-city-center-temple-baptism-font

- provo-city-center-temple-spiral-stairs

- provo-city-center-temple-construction-stairs-spiral

- provo-city-center-temple-construction-ground

- provo-city-center-temple-steeple-inside

- provo-city-center-temple-steeple-workers

- provo-city-center-temple-windows

- provo-city-center-temple-south-ground

- provo-city-center-temple-south-high

- provo-city-center-temple-south

- provo-city-center-temple-middle-floor

- provo-city-center-temple-middle

- provo-city-center-temple-window-view

- provo-city-center-temple-north

- Provo-Moroni1

- Temple-Open-House

- Gilbert-Temple-open-house-line

- Tegucigalpa-cornerstone8

| Temple Square is always beautiful in the springtime. Gardeners work to prepare the ground for General Conference. © 2012 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved. | 1 / 2 |

Once the decision is made to build a temple in a certain area, the First Presidency then prayerfully chooses the precise spot on which to build — a pattern that has been in place since the Church’s beginnings. For example, soon after entering the Salt Lake Valley in July 1847, Brigham Young identified the block of land on which to build the Salt Lake Temple. And more recently, after the Church announced in 2008 that it would build a temple in Kansas City, Missouri, President Dieter F. Uchtdorf of the First Presidency (at Church President Thomas S. Monson’s request) spent several days visiting many possible sites in the area. President Uchtdorf returned to Salt Lake City and recommended to President Monson the spot where the temple was eventually built.

Bill Williams, who has been a Church architect since 2003, says the Church looks for sites “that would have prominence, be in an attractive neighborhood, a neighborhood that would withstand the test of time.”

Design Phase and the Importance of “Sustainable Design”

After the temple site is selected and the Church determines how large the building should be (based on the number of members in the area), a team of Church architects creates potential exterior and interior designs.

While the purpose of each of the Church’s 140 temples is the same, many aspects of each structure’s inner and outer look and feel are unique, tailored to the local people and area. Williams says good architects "want to create something unique, something that has its own personality, and [Church leaders] allow us to do that” with temples. He adds that much can be done to make a temple unique, including “the decorative motifs, the kind of furniture, the interior accouterments, how articulate it is. It could be anything from the modern look that you see in the Washington D.C. Temple to something like the gothic, neoclassical look that you find in the Salt Lake Temple.”

To create a look and feel that is just right for a specific temple, architects solicit a number of sources. For example, as the Church has designed its future temple in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Williams says his team met with locals to “understand the nature of the people, the country that they live in, the Mormons that are there and how we can better fit the temple” to them.

A critical aspect of the planning process is “sustainable design,” a concept that Williams says seeks to reduce a temple’s long-term operational cost. “Whatever we can do to make the environmental systems, the mechanical systems energy efficient, to make the interior materials have longevity so that they don't wear out straightaway, anything we can do to conserve water, it's great for us as the owner because it makes that long-term cost less. That's what it means to be sustainable.”

And with a temple’s complex systems, sustainability is no easy feat. “We’ve got thousands of systems and components that all have to work in harmony,” says Jared Doxey, the director of architecture, engineering and construction in the Church’s Physical Facilities Department. “And getting everything the way it was designed at the highest quality, it's a very complex maze of issues that have to just be 100 percent right.”

In selecting building materials, the Church settles for nothing but the best. The pattern for this, Elder Walker says, is found in the description of Solomon’s Temple in 1 Kings 7 in the Bible. “They used the finest materials and the finest workmen to build the temple. And that’s the pattern we follow,” Elder Walker says. “Not to be ostentatious, but to be beautiful in a wonderful tribute to God.”

And the role of inspiration is most important to temple design, Williams says. “These are His houses, and we would like to make sure that everybody feels that responsibility, so that when we begin design meetings, we start with a word of prayer.”

The design process can take up to two years, and Elder Walker notes that all along the way — “from architectural detail clear down to colors and carpet swatches” — the First Presidency is involved and provides final approvals.

Construction Phase

Because of the high standards for building its temples, the Church sends representatives across the world to search out the best contractors. The Church uses more than a dozen contractors, and Doxey says “the complexity of the temple design requires the very best that most workers have ever had to give on a project.”

For example, Cory Karl of the Church’s Construction Services Division says that with brick masons, the Church asks “that they lay their brick in a rigorous way such that it's very uniform and consistent throughout” and thus “installed to the very best of the craftsman's abilities.”

Dustin Mundy, who oversees the steelwork on the Provo City Center Temple (including on its spiral staircases), says that while the desire to do his finest work comes naturally for such a project, he also has an extra measure of motivation: some of his ancestors built the spiral staircases in the Church’s Manti Utah Temple (completed in 1888). “It’s a blessing,” he says. “You want to do your most quality work, get the best journeymen that you can have on a job site and just do your best.”

The high building standards are in place for two main reasons: first, Latter-day Saints believe their temples are among the holiest places on earth and tributes to God; second, the Church builds these temples to last hundreds of years.

Church representatives ensure the construction companies are financially stable and able to meet Church regulations (including prohibitions against smoking, drinking and loud music on the construction site, though construction workers do not have to be Latter-day Saints). The Church then invites those selected companies to the bidding process. Once a company is chosen, construction typically takes 24 to 48 months, depending on the location.

For temple sites outside the United States, construction can take more time for a variety of reasons. “In some countries, there might be more manual labor to do things that in the United States we might have equipment to do,” Doxey says. And Karl adds that “other circumstances besides just the temple site” can slow down the process in some international areas, including additional fees incurred by local governments.

Although it can be a challenge to find qualified contractors, the high bar is worth it for both the Church and the workers. Not only do temple construction projects supply jobs in local communities, they also provide what many construction workers consider to be the zenith of their careers. For example, Doxey says the foreman of the concrete crew on the Church’s under-construction Philadelphia Pennsylvania Temple told him that in 30 years, he’s “never seen such a well-designed project” — one that he says is so durable that it “will be here when mankind is gone.”

Open House, Cornerstone Ceremony and Dedication

As was mentioned at the beginning of this piece, only Latter-day Saints who live the highest standards of the faith are permitted to enter a dedicated temple. Therefore, once construction is complete, and prior to the temple’s dedication, the Church opens the temple doors to the public for several weeks for free tours. These open houses are a rare opportunity for anyone in the community — Mormon or otherwise — to walk through a temple and learn more about Latter-day Saint beliefs.

Then, a week or two after the open house concludes, a Church leader (usually a member of the First Presidency) formally dedicates the temple. One aspect of the dedication events is the cornerstone ceremony, where Church leaders and others place mortar around the cornerstone to symbolize the temple’s completion. Later on, Elder Walker says, the president or the person he assigns says the dedicatory prayer “to consecrate the temple that it would be used for those sacred purposes for which the temple is built.”

A Beautiful Addition to the Community

At the Twin Falls Idaho Temple open house in 2008, Elder Walker remembers how community leaders and journalists referred to that structure as “our temple,” proving to him that a temple’s beautifully built structure and immaculately kept grounds are a source of pride for local citizens. In fact, experience worldwide demonstrates that Mormon temples positively impact neighborhood property values, even in a bad economy.

“I think it just shows that the temple, normally, will be one of the most beautiful —if not the most beautiful — building in a community. It’s natural that, not just members of our Church, but all the members of the community generally would be very pleased to have a temple there, and they would feel it’s ‘our temple.’ We hope that that would be the case.”