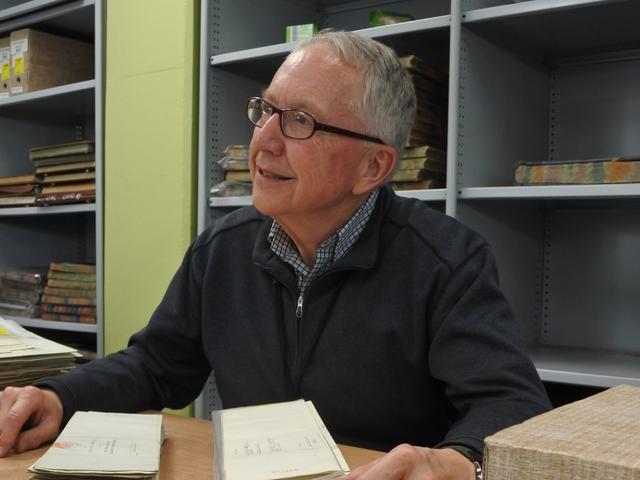

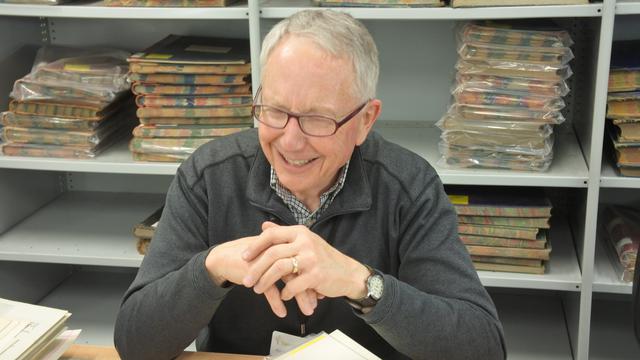

Garry Reynolds is returning to the United States with much more than he expected when he accepted an assignment from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to work in records preservation at the Public Record Office Victoria in Melbourne for his senior mission. During their eighteen months of volunteer service photographing court records at the PROV, he and his wife Sheila digitized over 500,000 inquests, wills, and probate records.

Satisfying as this has been for them, an even more rewarding experience has occurred. Garry found his Australian family. Here is his story:

My mother was Australian. She and my father met when he was here during World War II serving in the United States Merchant Marine. About the time they realized they were in love he was assigned to the Pacific and had to leave. They decided to get married by short wave radio and did not see each other again until she joined him in the United States after the war.

My father’s home was in Idaho, where winters are cold and snowy. She survived two Idaho winters and then wanted to go home to Melbourne, so we did. I was a baby then. We lived in Melbourne for a while and then went to Queensland, where my father worked in the Outback building fences in cattle and sheep stations.

During that time, we lived in tents and had all sorts of adventures. One day my mother came outside and found me playing with a death adder! After a year we went back to Melbourne and my parents ended up getting a divorce. When I was seven I went back to the States with my dad. We moved in with his sister in Oregon, and I grew up there.

When I was 20 I came to Sydney as a young missionary for the Church. My mother met my plane, my grandmother was there, and I had a terrific reunion with my Australian family. After serving two years in the Sydney mission, I went back home and did not return to Australia until 2015.

As we were preparing to come on this mission, we heard from a woman living in Melbourne who had found our name through FamilySearch. We confirmed we were cousins on my mother's mother's side. She said, “When you get to Melbourne we will have a family reunion," which we did. I met several first cousins there, and they gave me a book with a lot of history from that side of our family.

I also had the privilege of connecting through FamilySearch with a relative from my mother's father's side after we got here. Through him I met 20 cousins from that side I didn't know I had, as well as their children and grandchildren. They were avid genealogists and gave me a book of our family history with thousands of names in it, one of several such books I am going home with.

As my cousin and I worked on our family history together, we reached a sticking point: we couldn’t confirm who the original immigrant to Australia was. There were two different names. Were there two different women or one who changed her name? We had a marriage certificate for a woman we thought was our 2nd great-grandmother, Annie Quinn, who had arrived in 1852 on the ship Priscilla from St. Kilda’s Island in Scotland. But her name was not on the passenger list, and one of the children we thought was Annie Quinn's had Annie McQueen listed as her mother.

We were working from a photocopy of the list, which was old and blurry. My cousin came to the PROV, and together we were able to locate the original manifest, which was clear and readable. The name Annie McQueen was on the list, and it matched all the information we had. If I hadn’t been working at the PROV, this would never have happened.

We learned that Annie had come as a 9-year-old with her parents and their children. The Irish (and Scottish) potato famine was in full force. With the lure of the goldfields in Australia and their way paid by a wealthy donor on St. Kilda, they jumped at the chance to leave.

Unfortunately, St. Kilda was so isolated that the inhabitants hadn’t been exposed to diseases common in the 19th century and had no immunity. Half the people on the ship (142) died during the journey, including Annie’s parents and two younger siblings. Annie and her surviving siblings were orphans when they arrived.

The ship was quarantined for a year before the surviving passengers were finally allowed to leave. The two older teen-age brothers took off, probably for the goldfields, as soon as they could and were never heard from again. She also had an older sister who went with "friends," probably a family on the ship. They also have never been found. Annie went home with "A woman who lived on Collins Street," possibly named Quinn. We have not been able to identify that woman.

So, with that first immigrant confirmed, we were able to extend the family line back for generations and forwards to my mother. Through researching records at the PROV, we learned that my Grandmother Thornton had two older brothers who were killed in World War I in France, and her husband, my grandfather also fought in the war and was injured.

We are going home with books literally containing thousands of names of my deceased relatives. More importantly, we now know dozens of living relatives in Australia and have formed a bond with them we will treasure all our lives. We will stay in touch and hope to see them again when they visit us in America.

We couldn't be more thrilled or surprised that this has happened--all because we were assigned to work in records preservation in Victoria.